cancer and alzheimer’s disease The disease is two of the most feared diagnoses in medicine, but these diagnoses rarely strike the same person.

For years, epidemiologists have known that cancer patients are less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease, and that Alzheimer’s patients are less likely to get cancer, but no one could explain why.

a New research using mice suggests a surprising possibility: certain cancers may actually have negative effects protection signal to the brain to help get rid of toxic protein mass It is associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Related: Radiation therapy linked to lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease, study finds

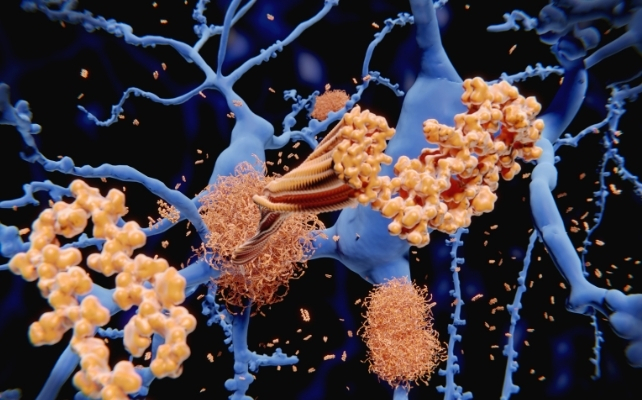

Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by sticky deposits of a protein called amyloid beta that accumulate between nerve cells in the brain. These lumps or plaques prevent you from: communication It invades between nerve cells, causing inflammation and damage that slowly erodes memory and thinking.

in new researchScientists implanted human lung, prostate and colon tumors under the skin of mice bred to develop Alzheimer’s disease-like amyloid plaques. Even if left alone, these animals surely As humans age, dense clumps of amyloid beta form in the brain, reflecting an important feature of human disease.

But once the mice carried the tumors, their brains no longer accumulated the usual plaques. In some experiments, the animals’ memory also improved compared to tumor-free Alzheimer’s model mice. suggest change It wasn’t just visible under a microscope.

The research team determined that this effect was due to a protein called . Cystatin-C It was being pumped into the bloodstream by the tumor. A new study suggests that cystatin-C released from tumors may cross cell membranes, at least in mice. blood brain barrier – A usually narrow boundary that protects the brain from many substances in circulation.

Once in the brain, cystatin C appears to attach to small clusters of amyloid beta, marking them for destruction by the brain’s resident immune cells called microglia. These cells act as the brain’s scavengers, constantly patrolling for debris and misfolded proteins.

In Alzheimer’s disease, microglia seem to lag behind and amyloid beta accumulates and hardens into plaques. In tumor-bearing mice, cystatin C activated a sensor on microglia known as Trem2, effectively switching them to a more aggressive plaque-clearing state.

surprising trade-off

At first glance, the idea that cancer “helps” protect the brain from dementia sounds almost perverse. However, biology often works through trade-offs, and processes that are harmful in one context may be beneficial in another.

In this case, the secretion of cystatin-C by the tumor may be a side effect of the tumor’s own biology, which happens to have beneficial consequences for the brain’s processing capacity. misfolded protein. That doesn’t mean it’s good to get cancer, but it does reveal a potentially safer pathway that scientists can use.

The study joins a growing body of research that suggests the link between cancer and neurodegenerative diseases is more than just a statistical quirk. large population the study reported that people with Alzheimer’s disease were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with cancer, and vice versa, even when age and other health factors were taken into account.

This led to biological concepts. seesawAs in cancer, the mechanisms that drive cells toward survival and growth can also steer them away from pathways that lead to brain degeneration. The cystatin-C story adds a physical mechanism to the situation.

However, this study was conducted in mice, not humans, and that distinction is important. Mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease capture some hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease, particularly amyloid plaques, but do not fully recapitulate the complexity of human dementia.

We also don’t yet know whether human cancers in real patients produce enough cystatin C, or even pump it into the brain, to have a significant impact on Alzheimer’s disease risk. Still, this finding offers interesting possibilities for future therapeutic strategies.

One idea is to develop drugs or treatments that mimic the beneficial effects of cystatin C without involving the tumor at all. That could mean a modified version of the protein designed to bind amyloid beta more effectively, or a molecule that activates the same pathway in microglia to increase its clearing ability.

This study also highlights how diseases can be interconnected, even when they affect very different organs. Tumors growing in the lungs or colon may seem a far cry from the slow buildup of protein deposits in the brain, but the molecules they release can travel through the bloodstream, cross protective barriers, and change the behavior of brain cells.

Related: U.S. cancer survival rate reaches milestone high of 70%

For people currently living with cancer or caring for someone with Alzheimer’s disease, this study won’t immediately change treatment. But this study offers a more hopeful message. By delving deeper into even devastating diseases like cancer, scientists may stumble upon unexpected insights that point to new ways to keep the brain healthy in old age.

Perhaps the most striking lesson is that the body’s defenses and failures are rarely simple. Proteins that contribute to disease in one organ may be used as cleanup tools in another, and by understanding these tricks, researchers could safely use them to protect the aging human brain.![]()

Justin StebbingProfessor of Biomedical Sciences; Anglia Ruskin University

This article is republished from conversation Under Creative Commons License. please read original article.