The problem of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is a concern for many medical professionals. As disease-causing bacteria adapt to our methods of reducing them, especially with antibiotics, an arms race ensues, and we appear to be losing it. Researchers aim to improve the situation by examining how bacteria adapt to antibiotics. Through analysis of large amounts of data, researchers including those at the University of Tokyo have discovered for the first time two different strategies that bacterial plasmids may use to share antimicrobial resistance with other bacteria. Computer analysis can help identify and predict risks, and future laboratory experiments could help researchers narrow down important areas for further investigation.

Bacteria, including those that cause disease, can evolve very rapidly. One reason for this is their ability to share genetic material among themselves, leading to rapid adaptation. This sharing of genetic material is done using small DNA loops released by bacteria called plasmids. Some plasmids can spread to a wide range of bacteria, while others are restricted to a small number of bacteria. And because they commonly carry genes for antibiotic resistance, understanding how plasmids spread is an important area of research.

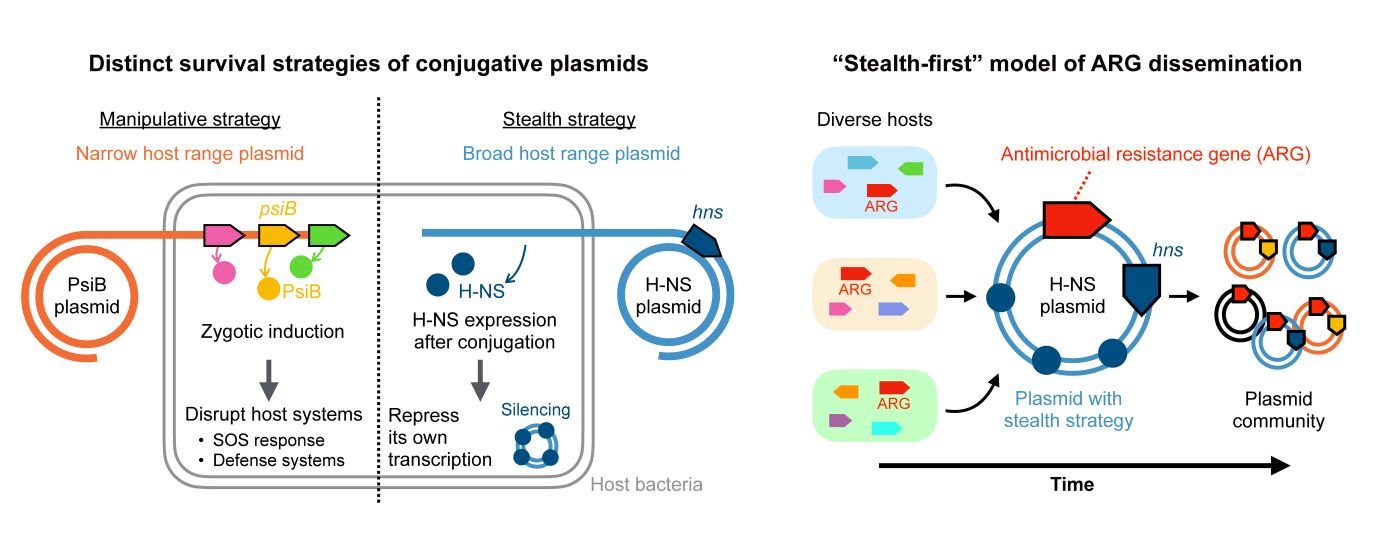

“Our latest research shows that plasmids follow two very different survival strategies. Some act stealthily, mostly silencing genes to minimize their impact, while others act manipulatively and actively interfere with the host’s systems to ensure their own survival,” said Ryuichi Ono, then an undergraduate student in the Department of Bioinformatics and Systems Biology. “By analyzing more than 10,000 plasmid sequences, we found a clear pattern: Stealth plasmids tend to find new antibiotic resistance genes first, and then engineered plasmids help spread those genes rapidly. We call this process ‘stealth first,’ and it may help predict how future resistance threats will emerge and spread.” ”

Ono and his team analyzed a variety of bacteria from the group called Enterobacteriales, which includes E. coli. They found that the two strategies, stealth and manipulation, rarely appeared together in the same plasmid, and that plasmids that used either strategy tended to carry more antibiotic resistance genes than plasmids that used neither.

“We identified specific genes, hns in stealth plasmids and psiB in manipulative plasmids, that correspond to low and high selectivity plasmids, respectively. Using these genetic signatures, we introduced the idea of ’plasmid survival strategies’ as a new framework for understanding how plasmids evolve,” Professor Ono said. “When we applied this framework to 48 major antibiotic resistance genes, a consistent pattern emerged. This structure explains past resistance outbreaks and may help predict future resistance outbreaks.”

This study provides a new model for understanding plasmid evolution and helps understand the relationship between plasmid content and its potential targets. The study revealed several potential vectors that can be detected and measured, which the researchers hope will lead to better tracking and prediction of emerging antibiotic-resistant infections. And the implications of two genes, hns and psiB, which are key components of this, may be useful targets for research to prevent the spread of antimicrobial resistance. However, it should be noted that this study focused on a single bacterial group and was based on computational analysis. Future studies across additional bacterial lineages, along with experimental validation, will be important to facilitate further discoveries.

“Our stealth-first model suggests that we may be able to predict future resistance threats by monitoring which genes appear primarily on stealth plasmids. If a resistance gene is still restricted to stealth plasmids and has not yet migrated to engineered plasmids, it may be about to enter the second stage of rapid spread,” said Naoki Konno, a graduate student in the Department of Biological Sciences at the time. “We are particularly excited about the possibility of using this framework as an early warning system. Many groups around the world are trying to predict how resistance genes move through bacterial populations, and we hope our work is a practical step toward that goal. Getting there will be difficult, but it’s a problem worth tackling.”