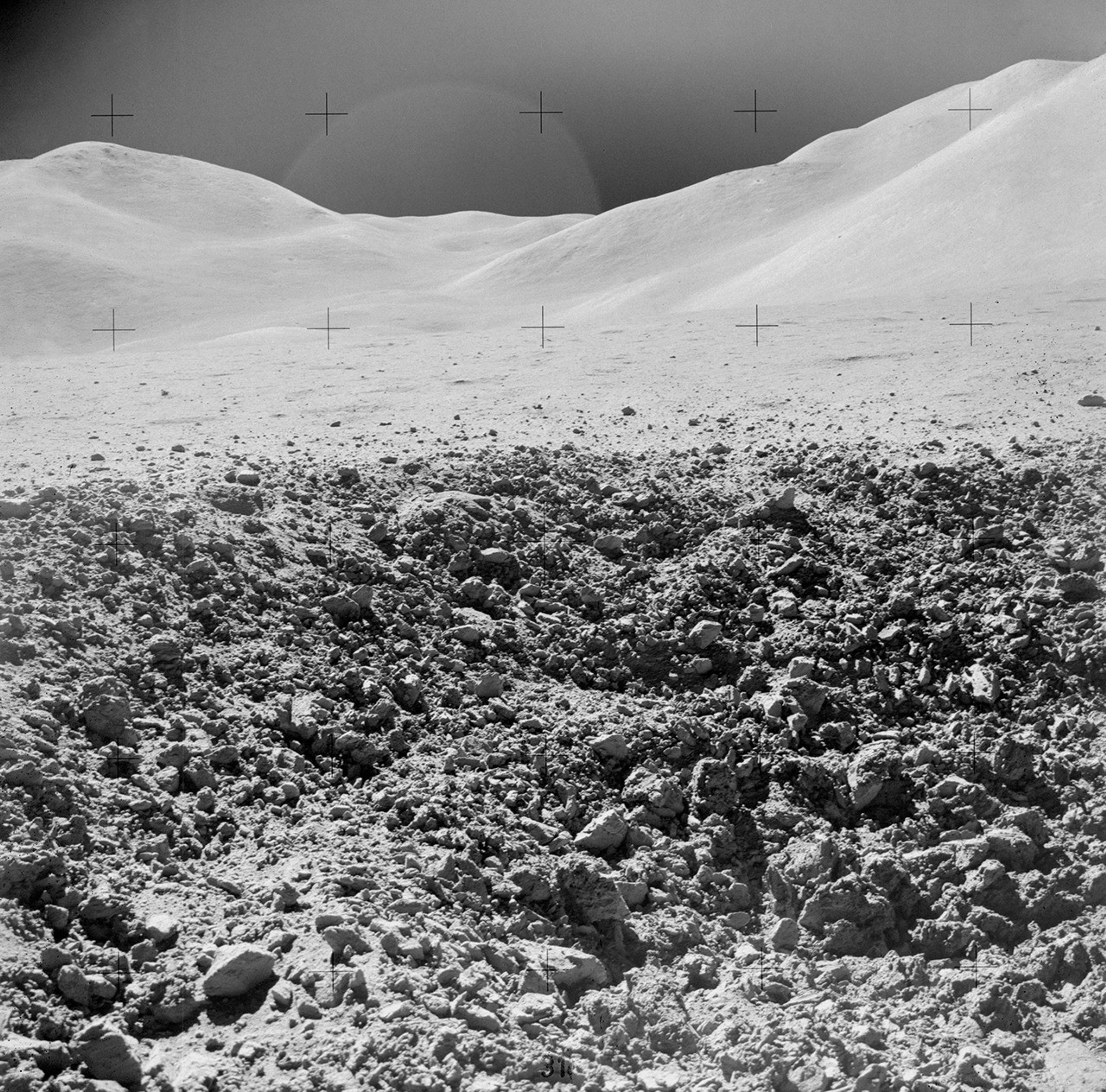

A close-up of a portion of a “relatively new” crater to the southeast taken during Apollo 15’s third lunar walk.

Credit: NASA

A new NASA study of Apollo lunar soil reveals the moon’s record of meteorite impacts and the timing of its water supply. These discoveries set an upper limit on how much water meteorites may have provided late in Earth’s history.

Previous research has shown that meteorites struck Earth early in the solar system’s development and may have been an important source of Earth’s water. In a paper published Tuesday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers led by Tony Gargano, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Johnson Space Center and Lunar and Planetary Institute (LPI) in Houston, used a new method to analyze the dusty debris that covers the moon’s surface. regolith. They learned that even under generous assumptions, meteorite strikes from about 4 billion years ago may have provided only a fraction of Earth’s water.

The Moon serves as an ancient archive of the traumatic history that the Earth-Moon system has experienced over billions of years. While Earth’s dynamic crust and weather erase such records, lunar samples preserve them. However, records do not come without challenges. Traditional methods of studying regolith have relied on analysis of metal-preferring elements. These elements can become clouded by repeated impacts on the moon, making it difficult to disentangle and reconstruct what was in the original meteorite.

Enter a highly accurate “fingerprint” that takes advantage of triple oxygen isotopes, the fact that oxygen, the dominant element by mass in rocks, is unaffected by shocks and other external forces. Isotopes help us understand more clearly the composition of the meteorites that impacted the Earth-Moon system. Oxygen isotope measurements revealed that at least about 1% of the regolith’s mass contains carbon-rich meteorite-derived material that was partially vaporized when it impacted the moon. Using these known properties of the meteorite, the research team was able to calculate the amount of water that would have been transported inside.

“The lunar regolith is one of the rare places where we can still interpret a time-integrated record of what was hitting Earth’s neighborhoods over billions of years,” Gargano said. “Using oxygen isotope fingerprints, we can derive impactor signals from mixtures that have been melted, evaporated, and reprocessed many times.”

This discovery has implications for our understanding of water sources on Earth and the Moon. When scaled up by a factor of about 20 to account for the much higher proportion of global impacts, the cumulative water represented in the model is only a few percent of the water in the Earth’s oceans. This makes it difficult to reconcile the hypothesis that a late arrival of water-rich meteorites was Earth’s main source of water.

“Our results do not imply that the meteorite did not provide water,” added co-author Justin Simon, a planetary scientist in NASA’s Johnson Division of Astronomical Research and Exploration Sciences. “They say the Moon’s long-term record makes it very difficult for slow meteorite inbounds to become a major source of Earth’s oceans.”

In the case of the Moon, the implied arrival from about 4 billion years ago is small on Earth-ocean scales, but not significant for the Moon. The moon’s available water inventory is concentrated in small, permanently shadowed regions at the north and south poles. These are some of the coldest places in the solar system and present a unique opportunity for scientific discovery and potential resources for lunar exploration as NASA lands astronauts on the moon with Artemis III and beyond.

The samples analyzed for this study were taken from the part of the moon near the moon’s equator facing Earth. Apollo program landing. Rocks and dust collected over 50 years ago continue to reveal new insights, but only on a small portion of the moon. The samples provided through Artemis will open the door to a new generation of discoveries for decades to come.

“I’m part of the next generation of Apollo scientists, people who didn’t participate in the mission but who were trained in the samples and the questions that were made possible by Apollo,” Gargano said. “The value of the Moon is that it gives us ground-truths: real physical matter that we can measure in the laboratory and use to solidify our inferences from orbital data and telescopes. I can’t wait to see what the Artemis samples can tell us and future generations about our place in the solar system.”

/Open to the public. This material from the original organization/author may be of a contemporary nature and has been edited for clarity, style, and length. Mirage.News does not take any institutional position or stance, and all views, positions, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors alone. See full text here.