We live near a cosmic fusion reactor that provides all our heat and light. This reactor is also responsible for the production of various elements heavier than hydrogen, which is true for all stars. So how do we know that a star is an element producer? A star’s spectrum contains fingerprints of the different elements cooked up by the star, so it hides many clues.

Hints about the production of carbon and oxygen, in particular, have long been hidden in data sets obtained when searching for planets around nearby stars. Astronomers suggest that such stars may exist. A place to look for exoplanets. Thanks to the brainstorming of astronomer Dario González Picos of Leiden University in the Netherlands, he and his research team looked at high-resolution spectra of nearby stars to look for rare isotopes of the two elements.

The research team studied 32 million dwarf stars, one of the most common stars in the galaxy. They live for a long time on the main sequence, a period during which a star fuses elements at its core. A star’s atmosphere preserves traces of chemical evolution from its birth to its current state. The stars studied exhibit rare isotopes of carbon and oxygen, which tells us something about their evolution. The team’s findings represent a step forward in understanding the production of elements and how they are dispersed as part of stellar evolution.

Stellar Seed of Elements

Carbon and oxygen are abundant in the universe. Like all life forms on Earth, we are carbon-based and contain carbon as a constituent. We breathe oxygen produced by other life forms on Earth. So it’s natural to wonder how these two came about during stellar evolution. This means we also need to understand the complexity of the element formation process in stars.

“Nuclear fusion in stars is a complex process and is only the starting point for chemical evolution,” said study leader Dario González Picos from Leiden. This process is called stellar nucleosynthesis, and all stars undergo it. For example, our sun fuses hydrogen to make helium and will continue to do so for billions of more years. There will then come a time when the hydrogen in the nucleus will run out and the helium will begin to fuse into heavier elements such as isotopes of carbon and oxygen. At that point, it becomes a reddish star and strong winds send its elements into space. Stars much more massive than the Sun do the same thing, but when they explode as supernovae they produce even heavier elements.

Essentially, the stars are part of a larger cosmic recycling project that enriches galaxies with material to create new stars and planets. Their light conveys all the history they have experienced through the chemical fingerprints left behind by the creation of new elements.

find a rare fingerprint

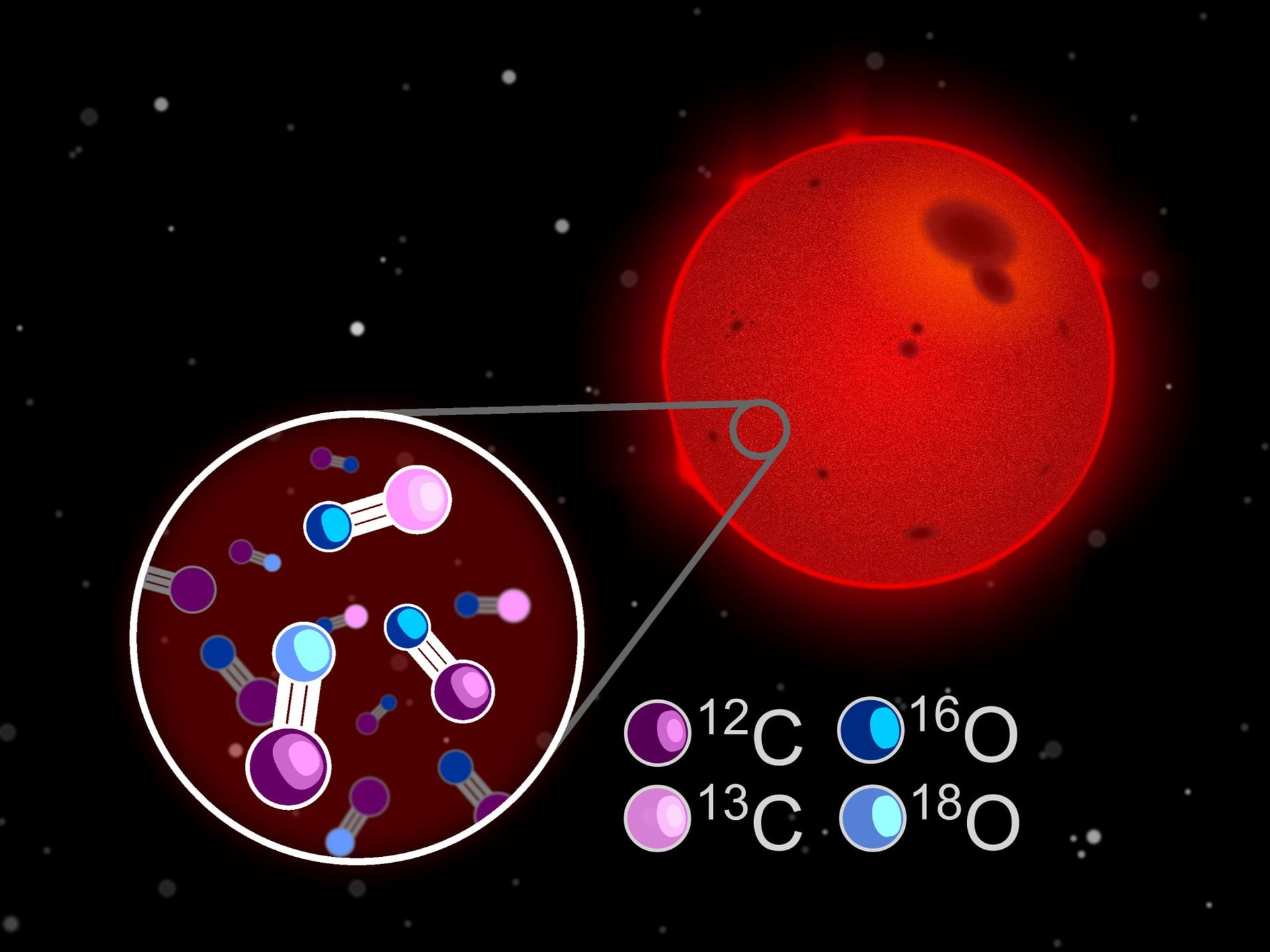

González Picos collaborated with Ignas Snellen and Sam de Regt to detect and read chemical fingerprints under starlight using carbon and oxygen isotopes. These are different types of elements and differ in the number of neutrons in their atoms. For example, 99% of carbon atoms on Earth have six neutrons, but only a small percentage have seven. The research team was able to measure the carbon and oxygen isotope ratios of 32 neighboring stars with unprecedented precision. The way they did it was by sifting through the data archives of the Canada-France-Hawaii telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawaii. The data included stars with effective temperatures between 3000 and 3900 K that showed strong signals of heavier elements (i.e. had strong metallicity in their atmospheres).

*Artist’s impression of red dwarf isotopes. Credit: Kutay Nazli*

*Artist’s impression of red dwarf isotopes. Credit: Kutay Nazli*

“We now know that stars that are less chemically enriched than the Sun have lower concentrations of these trace isotopes,” de Legt said. “This discovery confirms what several models of the chemical evolution of galaxies have predicted and provides a new tool to wind back the cosmic chemical clock.”

“This observation was originally made for a very different reason than why we’re doing it now,” Snellen said. “It was actually Dalio’s idea entirely to use high-resolution spectra intended for planet discovery for this isotope study, and the results were fantastic.”

As Gonzalez-Picos points out, the results provide another way to use stellar chemistry to track the evolution of other types of the universe. “This cosmic detective story is ultimately about our own origins, helping us understand our place in a long chain of astrophysical events and why our world looks the way it does,” he said.

For more information

Rare isotopes from nearby stars offer new insights into the origins of carbon and oxygen

Signs of chemical evolution in rare isotopes of nearby M dwarfs

Signs of chemical evolution in rare isotopes of nearby M dwarfs (arXiv preprint)